An Introduction to Decision Theory

First, a caveat. I am not a mathematician, I just use their tools sometimes. This post does not cover the axioms of decision theory, and does not cover probability theory with much rigour. Reader beware.

I’d like to give a minimal outline of Decision Theory and how it can be applied. Decision theory[1] is the multidiciplinary application of probability theory which describes how individuals rationally act under uncertainty. It is a formalisation (with many sets of axioms and tools to chose from) of how we choose an action to maximise the good of an outcome (the utility) or minimise the bad (the loss, an equivalent but opposite framing).

People can be right without reasoning, or reasonable without being right. Placing all your earnings on Twelve Black at a roulete table is a bad decision [2] but you might win a lot of money. Or you might chose to have an almost-always-successful medical proceedure and have bad results. Decision theory focuses on rational decisions with respect to an understanding of the options available and what you value.

Making Decisions…

Let’s start with an intuitive case. The following utility table lays out the actions (operation or no operation) and world states (outcomes failed, succeeded) for some hypothetical procedure. We do not know the outcome in advance.

| Succeeded | Failed | |

|---|---|---|

| Operation | Normal life span | Death |

| No Operation | Death | Death |

Intuitively we would say option #1 (operation) is always the best option; it has a better outcome than all other options. Formally, given a measurement function of how “good” an action and an action and , action is strictly dominant against action if

for every outcome where is the set of world states (outcomes).

What is a utility function? Conceptually, it measures how satisfied you are of some outcome; getting tea instead of coffee, losing roulette vs winning. In practical terms it is a real-valued cost function that establishes a ranked preference relation between all outcomes.

Note: Decision theory formalises rational decision-making but there are many decisions to make when choosing to model situations using it. Do not treat being handed €1,000 and a 50:50 chance of €2,000 or €0 as equivalent as a basic utility model would state. Small formulae do not adequately capture human psychology, value, and uncertainty. The map is not the territory.

…Under Uncertainty

Let’s model the decision to pet a neighbourhood cat with a utility matrix (don’t do that either). This is an alternative notation for simple utility functions. All of the utility numbers in this post will be fairly arbitrary.

| Friendly | Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Pet the Cat | Purrs (+100) | Scratch (0) |

| Don’t | Saw Cat (+10) | Saw Cat (+10) |

What do we do? We do not know if the cat is friendly, it might scratch us. But cats are cute. Maths, our friend, will help us decide.

If we belive the world is against us and that we have rotten luck we should minimise losses. We would use the maximin decision rule and choose the action with the best worst-case. If we don’t pet the cat we will not be scratched, at least.

The “utility” of this encounter depends on the demeanor of this particular cat. But the world is uncertain; we are not predestined to being scratched, not every cat is mean, and we should reason more probabilistically. If some percentage of cats are friendly and (this definition will be reused) are mean, the expected value (average) of our utility function for each action is:

We should pet the cat if , which is true if at least ten percent of cats are friendly. This is true, marginally.

- Friendly, petted.

- A bit friendly, but I was warned the cat bit several people.

- Friendly, loafing in peace.

Cat break over; we’ll continue developing our toolkit. We guessed at least ten percent of cats were friendly, but a cat’s friendyness is also conditional on the action (petting, not petting). We should look at probabilities of outcomes conditionally depending on the action we take.

The general formula for utility of an action is

or; the average utility of for action is the sum of the probability of each outcome given action times the utility of outcome . In our example, the probability would represent how likely the cat is to be mean or friendly if we chose to pet it (or not). Cats are variable creatures and our knowledge is imperfect; how do we figure out this prior probability?

We generally have guesses, even ill-informed and blurry ones. I like to factor these uncertain prior beliefs into decision-making. I’ll introduce two new tools:

Diversion One: Random Variables

Random variables are not random and not variables. This is a bad start, but the term stuck. Random variables are functions that map world-states to a numeric value; the world is random, the function returns a number based on the world state. They are usually denoted ,, or some other capital letter. would be a realised value (numeric description) returned by the random variable . They model uncertainty:

- = # scratches from a cat

- = whether cat purrs () or ()

We can ask probabilistic questions by phrasing them with random variables; for example, what is the probability the cat purrs

we can phrase these probabilistic questions conditionally; “what is the probability of cats purring given I pet them?” is written

Diversion Two: PDFs and PMFs

Probability distributions, not the file format. There is a large taxonomy of PDFs and PMFs, and a lot to dicuss about how model with them, analyse them, combine them. More than I can cover here. I’ll describe the basic idea, starting with PMFs.

Probability mass functions (PMFs) are functions that give the probability that a discrete random variable realises some exact value. They also sum (or integrate for PDFs) to one (since all outcomes are in there, the sum probability is one). While this is a simple requirement, there is no obligation for the world to give simple answers to the question. The probability a cat purrs or doesn’t is … hard to model precisely algebraically.

The reality is we often make an approximation of the world when modelling probabilities. The odds of getting a heads / tails when flipping a coin depends on the shape of the coin, any subtle deformation, any bias in how it’s flipped, wind currents in the room, and infinity other factors. In practice, we give the caveat “flip a fair coin” and give it 50:50 odds of heads or tails. That brings us to our first PMF, the Bernoulli distribution.

Probability distributions are parameterised. If you plot out probability on the y axis and outcome on the x axis, and adjust probability distribution parameters, the shape of the distribution would change. Some outcomes might be more likely than others, all outcomes equiprobable (the uniform distribution), some outcomes inevitable. Our first (well, second now) distribution is modelled with a single parameter . It models a true / false experiment with probability of true, and as false. We can model coin-flips this way, and any events with a fixed probability of happening / not happening.

PMFs are discrete, Probability Density Functions (PDFs) are continuous and it tells us the probability that random variable has a realised value of in some interval (e.g ). They cannot tell you the probability that a value has the exact value ; instead, they deal with ranges. They can model probabilities of heights, speeds, and other continuous random variables and are otherwise conceptually similar to PMFs.

We’ll discuss some of the probability distribution zoo later, but broad points; they describe the probabilities of outcomes of a random variable, they are parameterised, and they are generally simplifications we make to describe the world. With different starting assumptions, we model the probabilities of realised values from random variables using different probability distributions.

Why bother? By modelling random variable (representations of some world-state in numeric form like “decibel of purring”) as probability distributions we get access to a toolkit of analyses for that particular distribution which lets us answer questions like:

- : What is the probability of a bad outcome if I take this action?

- : How likely is it I get scratched if I pet the cat?

- : What is the expected utility this action?

These questions cannot be answered without computing a probability distribution of how our actions affect outcomes; . We are discussing Decision Theory; how to act rationally under uncertainty. Utility functions describe what we want, and probability distributions tell us what to expect. To make decisions rationally with these tools, and understand how our actions affect outcomes, we have to model uncertainty beyond “idk 17% of cats are mean”; we lose so much information boiling down probability models to a single point-estimate.

- Friendly, jumped in my window while I was sleeping and lay on the bed purring

…Under Less Uncertain Uncertainty

Lets apply our tools to a new example; Pandas. Pandas eat an inordinate amount of bamboo and sleep a lot. You’d like to see the panda eating bamboo and not sleeping, and model a utility table as such:

| Panda Awake | Panda Asleep | |

|---|---|---|

| There | Panda! (+100) | No Panda! (-20) |

| Elsewhere | Missed Panda (-10) | Other things to do (+10) |

you would like to see a panda, but turning up for it to be asleep hidden in a corner would be disappointing. What are our odds of seeing the panda, and how do the utilities balance out? Let’s start with what we know about panda’s sleep-cycles and then define terms. According to a quick google search, pandas sleep about eight to ten hours a day and nap a lot to conserve energy.

denotes whether our panda is awake () or asleep ().

is the (unknown) fraction of time our panda is awake. We can model as a Bernoulli trial of .

We don’t know precisely how sleepy this panda is, but we have some initial notion about it. We can model our prior belief about using a beta distribution

Thanks, Wikipedia!

Beta distributions are probability distributions with two parameters and . We can adjust the parameters to set the mean . They have the useful property that we could describe many distributions with the same expected value for different levels of certainty by adjusting , by a shared constant factor. If we had read thorough scientific papers about panda sleep cycles (I haven’t) we could tightly centre the beta distribution around the expected value. I think that a panda’s wakefulness can be modeled by

Let’s get back to deciding whether to see the panda. We have actions

and world states

and have a probability distribution modelling how likely our panda is to be awake. The expected utility of our actions is conditional on

With being the expected utility.

We would choose trying to see the panda vs the alternative iff

We don’t know what is but have a prior belief that . We’ve also implicitly shifted from deciding to minimise the worst case to a new decision criterion of maximising expected utility. This approach is the Bayesian expected-utility decision rule; choose an action that maximised ; that is, choose an action that maximises expected utility across all outcomes . This fits human behaviour better than maximin; we generally prefer to do what’ll probably work out the best.

The expected value of our beta distribution is , so under expected utility maximisation it’s rational to try and see the panda. We’ll probably see the panda, and risks of not seeing it aside pandas are cute and Hope Springs Eternal

Attempt #4 and worth it ❤️

It’s worth trying to see pandas several times even with imperfect odds. But we’ve acknowledged and captured the uncertaintly in our model and in a way discounted the risk of not seeing a panda. Expected-utility maximisation is risk-neutral and focuses on expected utility alone.

Can we make decisions that accounts for a distribution rather than its expected value alone?

…Less Uncertainty, Please!!

Sometimes people operate intercontinental nuclear missile silos instead of idly seeking out pandas. They await warnings for whether there are missiles inbound and a retaliation order might be sent in response. But, there are sometimes false alarms. Action utilities can be modelled [3] as

| Attacked | False Alarm | |

|---|---|---|

| Launch | ||

| Verify |

In the case of pandas it’s not so bad missing them and the upside is great (I mean look at the panda, very cute). On the other hand, accidentally incinerating Paris and Berlin and Madrid and Lisbon and Toyko and New York and Lagos, and killing billions of people and salting the lands of earth for dozens of generations due to an alarm blip is more bothersome and would require some explaining. Nuclear Command & Control also need to make decisions, and ideally rationally versus a-la-Strangelove.

We’ll escalate from modelling cats and pandas to modelling thermonuclear war.

- We have two world states: , attacked or false alarm

- We have an alarm signal

- We have a belief , the probability of the alarm being accurate

Under expected-utility-maximisation, if were known

we “should” launch iff , which works out as being rational when

If we are more than 38% certain it’s a real attack, launch the missiles! Alas, Babylon[4]! Bombs away!

A More Considered Approach to The Apocalypse

Nuclear defense and retaliation is an uncertain business. We do not know , which has subfactors of the actual base-rate-of-nuclear-attacks and sensor-reliability:

- : whether some enemy a continent away truly did launch first.

- alarm true positives

- alarm false positives

Given these prior probabilities, we can compute the posterior probability an alarm is real using Bayes rule

and what are the probabilities of an enemy launching, or the alarm being accurate or going off erroneously? 🤷♀️. Where uncertainty enters, move from using a point-estimate probability to modeling that uncertainty itself with distributions

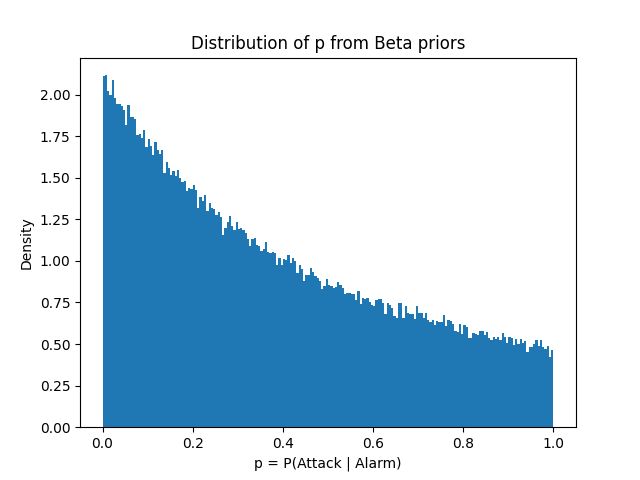

We’ve formulated (apart from choosing alphas and betas), how do we get probabilities out of this formulation? Not analytically, but numerically; sample from their Beta priors and approximate probabilities from the observed distribution. Let’s guess some priors and compute :

, ,

We’ve computed , and can see that occasionally our alarm is quite reliable (e.g ), but it’s almost always only somewhat reliable. The expected value is reliability, over the long run, but in the long run we are all dead. In the short run too, if we behave like we are maximising some multi-trial utility than facing a single prospective incoming missile. We get one alarm and one decision. The behaviour we see here is “the alarm works great! some of the time, not normally though!”, shouldn’t be flattened to “38% accurate”. The alarm is more noise than signal.

We want to make the risk of catastrophic error extremely small and act in a way that minimises catastrophic error. When a mistake can end the world we can’t just maximise utility over time; we need to act to avoid disasters, even if they are rare. This is a safety first stance.

In this situation, faced with uncertainty and enormous risk, we should do as Stanislav Petrov did in the same situation; refuse to murder billions of unwitting people. His decision was mostly well-received. [5]

This squirrel has no relation to nuclear risk management

Balancing Uncertainty and Utility

In our previous example we saw that rational actors don’t just maximise satisfaction with the expected outcome; they account for risk and uncertainty especially when there are rare but catastrophic outcomes. Let’s move back to DEFCON five and discuss pill repackaging.

A hospital pharmacy repackages tablets into one-dose-pouches, and they need to verify that they dispensed the right pills for the prescription. They have two options to choose between. There are two machines

Option A: Cheap to Run

| Action | Correct pill | Wrong pill |

|---|---|---|

| Keep | -1 | -1000 |

| Reject | -5 | -5 |

Option B: Expensive to Run

| Action | Correct pill | Wrong pill |

|---|---|---|

| Keep | -3 | -1000 |

| Reject | -5 | -5 |

Both machines do the same work; keeping or rejecting pills. The cost of failure is the same, and very high; hospitals should not dispense mystery pills to patients. But the first machine is cheaper to run, so we lean towards using it.

The accuracy of a machine is ; the probability that a pill it keeps is actually correct. is not a single number; operating conditions change, staff changes, lighting changes, and many other factors make performance vary. We represent that variability with a distribution over ,

For each pill, denotes “right” or “wrong”. Each pill selection is an independent trial conditioned on accuracy . We represent the uncertainty about with a probability distribution . Each pill processed is an independent trial conditional on

,

We have accuracy distributions for each machine

,

Both machines are measured to have the same accuracy

So should we use the machine that’s cheaper to run?

In the last section I made the point that when there are catastrophic outcomes, we ought to consider how to avoid disasterous outcomes rather than saying “well, on average it works” and blindly maximising utility. This is ultimately a political and engineering choice, though; safety first (avoiding disaster even at some potential cost) or safety last (crude utility maximisation with disaster avoidance as an afterthough)

There’s a problem

Our cheaper machine works on average, but occasionally and unpredictably performance is abysmal. “it works on average” is not reassuring; to make the same joke twice, if we dispense the wrong medication to someone they don’t think about about utility-payoffs maximisation; they die. The cheaper machine works by a crude bar, but we have no basis to trust the cheaper machine on account of how variable its performance is.

For non-critical applications, choosing a cheaper machine with mixed-bag often-acceptable results might be rational, especially if it dramatically increases expected utility. But when mistakes matter, when “what could go wrong?” has unpleasant answers, for jobs where we are expected to uphold high standards, responsible people will not trust do-anything machines to run safety-critical tasks.

We should pay extra not for higher average performance, but to reduce the risk of disaster out of basic decency and responsibility.

This entire blog-post was written to teach how to conceptually risk-model whether to use LLMs in an automation. I’ve felt that too often people focus on whether they can simply do a task at all instead of how repeatedly, how reliably, and how independently, with how much trust. LLMs can do many tasks; we should always consider “how reliably”.

Please, think of more than the average-case behaviour when applying LLMs to safety-critical infrastructure. They may[6] handle medical diagnosis, financial analysis, fraud detection, eating disorder hotlines, and therapy sessions well on average, but what do the worst-cases look like? Life-ruiningly bad. Ethical, competent engineers build systems that work and work reliably, especially when lives are at stake.

Pet cats, though.

A happy cat

Asides

[1] Normative or prescriptive Decision Theory, that is. Studying what people actually do is another branch of Decision Theory.

[2] Under most but not all financial planning methods or measurements of subjective value.

[3] Utility functions can be subjective, this is not my personal stance on nuclear retaliation. For me I’d double-check before ending the world, but perhaps to each their own.

[4] I’m not recommending the book, but it’s a good expression.

[5] This story might be overblown, like most good stories.

[6] May is a broad term. It’s a separate fight that’s far more nuanced and devisive than (I hope) my own simple plea.

References

- An Introduction to Decision Theory, Martin Peterson. This book gave me an overview on the philosophy of decision theory and the many choices that can be made when modelling, and paradoxical outcomes.

- A Tutorial Introduction to Decision Theory, D. Warner North. https://www2.stat.duke.edu/~scs/Courses/STAT102/DecisionTheoryTutorial.pdf

- Wikipedia

- My notebook

- Reviewed (never written) by GPT, due to the expected utility gain of writing this faster and absence of catastrophic risk beyond saying something incorrect (high prior likelihood). It mainly fixed my terrible attempts at writing correct notation for distributions